Your Kid Is Safer Than You Think

Ditching the ‘stranger danger’ mindset for self-possession

I’m fresh off spending a couple of weeks with my in-laws, a visit that was mostly unremarkable in the way many family visits are. There were shared meals, overlapping routines, and contained conversation. But beneath that ordinary, I found myself face-to-face with something my partner has long shared a one-sided version of — the suffocating grip of fear that so many modern parents wrap tightly around their children, mistaking it for love.

My partner has described his upbringing as one of constant surveillance. Not care — surveillance. His parents would interrogate him about where he was going and with whom, check in compulsively, sometimes even give him walkie-talkies or a crappy phone, an early iteration of a tracking device so that they could know his whereabouts at all times, even when he was just a few blocks away at the playground or a friend’s house within the sub-development they called home. They were always certain they were acting out of deep concern, but what I saw was control and mistrust masquerading as protection and vigilance.

During our visit, they recounted, almost proudly, an incident from their past parenting vault that left me chilled. His mother — a former pediatrician who specialized in abuse cases — shared with her husband that when a child is in real danger, when a stranger attempts to abduct them, they often don’t scream. They comply. Silenced by fear, they freeze.

His father, apparently in a state of disbelief and attempting to prove her grim theory wrong, decided to “test” it. He found his opportunity in an old-school video rental shop, where he crept up behind his then four-year-old daughter, wrapped his arms tightly around her chest, lifted her off the ground, and began to back away. She didn’t cry out. She didn’t flail or kick. She simply turned her face, wide-eyed, toward her mother, silently pleading for help with the kind of wordless desperation that no child should ever have to feel outside of real danger.

They told the story as if it were a parable, proof of a bitter truth about the human nervous system. But I sat there stunned, and finally said what felt obvious to me. “I’m sorry, but that’s one of the most messed up stories I’ve ever heard. That’s not something I’d ever want to do to my kids, because I need them believing that most people are good. You know, that if they need help, someone will absolutely step in and help them.”

I didn’t say it with judgment, but with an exasperated sadness I couldn’t conceal. Because the worldview that makes that kind of “experiment” seem rational is one where the worst-case scenario isn’t just possible — it’s presumed. And not just presumed, but used to justify every act of control and suspicion that follows.

Later, his mother chimed in with her own story, a classic tale of maternal panic in a Walmart. She lost track of her youngest daughter, also a pre-schooler at the time, after the little one had followed my partner, then nine, to the bathroom, but ended up alone and confused instead. For several minutes, his mom was convinced that her daughter had been abducted — snatched away. “I thought I’d lost her forever.” But then, as is almost always the case, a kind, fellow shopper arrived with the tear-streaked girl in tow. Yes, she’d wandered off, but either by her own instinct or the help of a well-intentioned stranger, she’d found her way back.

What struck me most was not the temporary chaos of the moment, which every parent has experienced in one form or another, but the way the story was used. Not as an example of community or compassion or the power of a child’s inner compass — but as a reason to believe that everyone is always on the verge of disappearing. That safety is fleeting, and the worst is always waiting.

But that’s not the world we actually live in.

We live in a world where the overwhelming majority of children make it home every day. A world where kids get lost and then found, where neighbors help each other, where strangers return dropped wallets (happened to me this month!), and Walmart shoppers stop what they’re doing to reunite lost daughters with their panicked mothers. That’s the part we don’t say aloud. The part that doesn’t get headlines or emotional capital.

If you asked a hundred parents in any given town to call in each evening and report whether their child made it home safely, the lines would go quiet with sameness. “Yes. Home safe and sound. Again.” I could imagine the more than occasional, “He was a little late from practice, but yep, he’s back now.” The overwhelming, boring, beautiful norm would be safety.

But instead of anchoring ourselves in that truth, we let ourselves be shaped by outliers, by horror stories repeated until they feel commonplace. It’s a kind of collective trauma response, one that’s being unquestioningly passed down to the next generation.

What gets lost in this culture of constant vigilance is something crucial — a child’s sense of agency. Their ability to trust their instincts, interpret risk with nuance, and navigate the world with confidence rather than fear. Children who are taught that danger is omnipresent don’t become more prepared — they become more anxious, avoidant, and dependent. They internalize that the world is inherently unsafe and that they’re ill-equipped to handle it.

There is mounting evidence that this kind of fear-based parenting has its share of negative consequences. Rates of anxiety, depression, and mental health struggles among children and adolescents have been rising sharply over the past two decades. At the same time, children’s independence has been systematically eroded. Fewer walk to school, or play outside without adult supervision. And fewer still are trusted to solve even small problems on their own.

While parents are fixated on rare threats — abductions, predators, dark alleys — true dangers are going largely ignored. One of the greatest risks to a child’s health today is not strangers. It’s sedentary living, ultra-processed food, and disconnection from nature. It’s the slow erosion of resilience and confidence. Obesity, loneliness, and screens pose far greater threats to our children’s futures than the hypothetical man in the van. And unlike the van, those threats are here now. In fact, those threats were not warded off in my partner’s family. They were quiet, cumulative, and honestly, haven’t even been pegged as threats.

None of this is to say that caution has no place. Of course there’s wisdom in preparation, and it’s our responsibility to teach our kids about boundaries, awareness, and listening to their gut when something feels off. But preparation isn’t fear. There’s a world of difference between teaching a child how to find help and teaching them that no one will help. Between showing them how to use their voice and teaching them that no one is listening.

I want my kids to learn the subtle cues of their own intuition, not in a state of hypervigilance, but in a spirit of self-trust. I want them to believe that they can speak up and ask for help, and that people — most people — will respond with kindness. I want them to believe they belong in the world, not that they’ve got to hide from it.

Do I have to silence mom anxiety? I absolutely do. I have to remind myself that they’re safe, and more importantly, that they are worth trusting to make it to the shop three blocks away and back home without incident! That if something were to go wrong, it’s not the end of the story, but rather the beginning of a solution that they are capable of finding.

When we parent from fear, we don’t raise safer kids — we raise more fearful ones. We take away the slow and necessary process of learning to navigate risk, failure, and uncertainty. We shrink the world for them before they’ve even had a chance to explore it.

So no, I won’t sneak up on either of my girls to simulate an abduction, and I won’t treat every outing as a potential crime scene (even if my intrusive thoughts might wander there). I will prepare them as best I can, yes. I will teach them to look people in the eye, to speak clearly, to notice their instincts, and to act accordingly when something feels wrong. But I will also let them walk ahead of me, and make friends without vetting their family tree. I’ll let them feel at home in the world they were born into.

That, to me, is real safety — not the absence of danger, but the presence of courage. And I believe that courage grows best in children who are trusted to learn, listen, stumble, recover, and just get on with the act of living their lives.

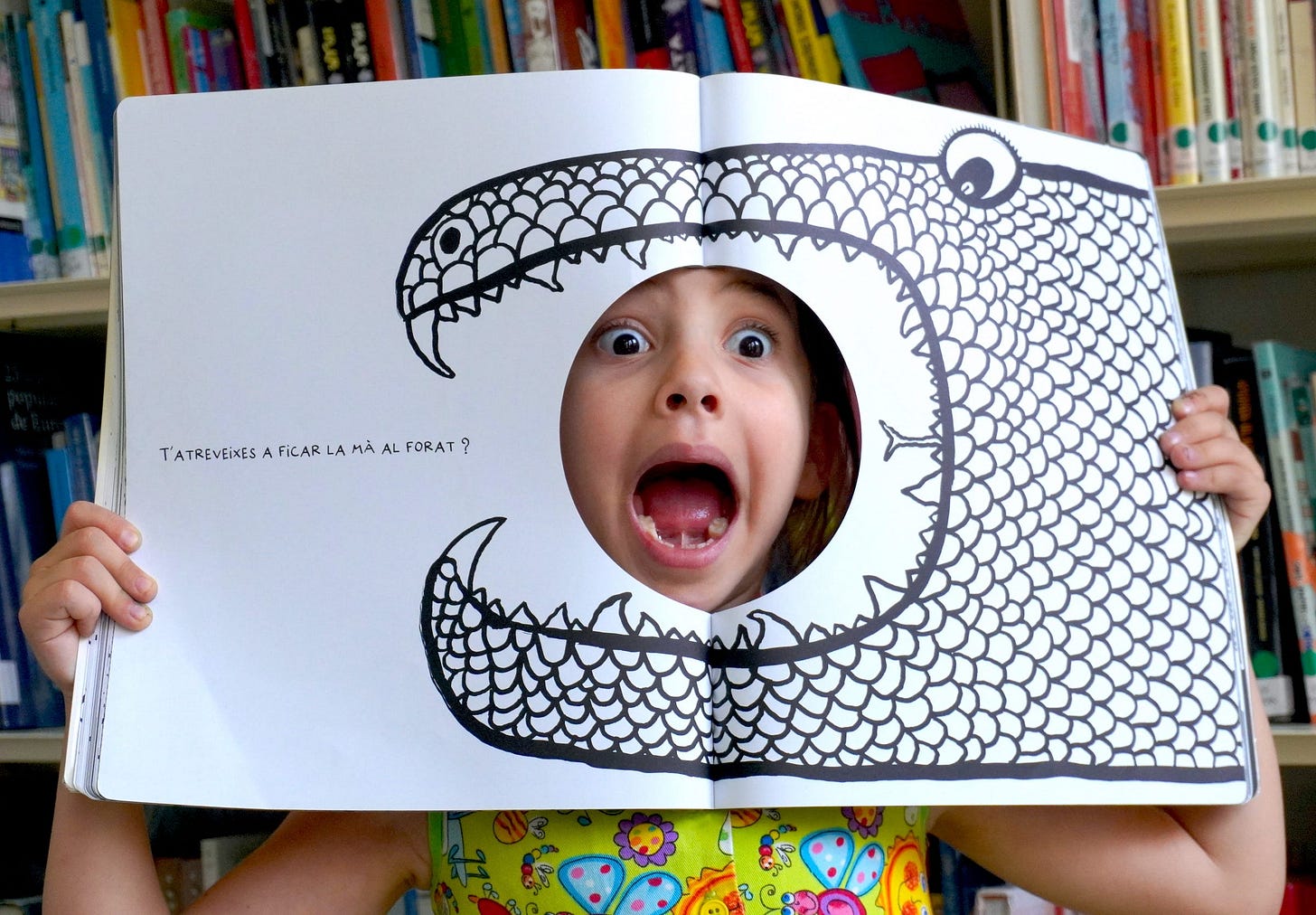

Thank you for reading and being here! Are you getting tired of having heart to hearts with me? I can do nothing but ask you to click the button if and when you feel the urge to be a patron of the arts (and snacks). Otherwise, please enjoy an early scribble of my daughter’s and hang out in the comments below.

Such wise words Abby, and I commend you on your approach to parenting. I always applied this ‘hands off’ where ever possible and my kids grew up to be resilient and confident individuals. It took me a while to stop blaming myself for Dom’s suicide…I was casting around for reasons and worried I’d ‘left him to it’ too much. But my other 2 children have helped me see that they feel they really benefitted from me not ‘helicoptering’ around them…

Anyway, back to your article! It reminded me of the conclusion a recent radio programme came to. It was about children being picked up by strangers in the street. The reality is that the people doing this are actively preying on the less confident, less streetwise kids. The ones that get overprotected basically. Go figure 😳

Yep, sounds like great mothering to me Abby 💪

Thank you for your considered response too in relation to Dom. It’s obviously always on my mind…the ‘why’ he felt as he did. I agree that it can run very deep, this search for a meaning. He was a ‘creative’ and unfortunately I think these personality types can often succumb to depression. Your reference to a ‘permanent loneliness’ very much resonates with how I saw him look when he was in a downward spiral.

I look forward to reading more of your posts Abby, you write really well.